Working with carbon steel has a few more steps that working in mild or stainless steels, since you need to heat treat to harden the material. In general this has two stages, the “quench” stage and the tempering stage. Of course once armour is heat treated it needs to be cleaned up (unless you are getting the heat treatment done in a vacuum kiln) and all of the work that you need to do to shape the metal really needs to be done before heat treatment – because once it is heat treated it will be very hard and difficult to move.

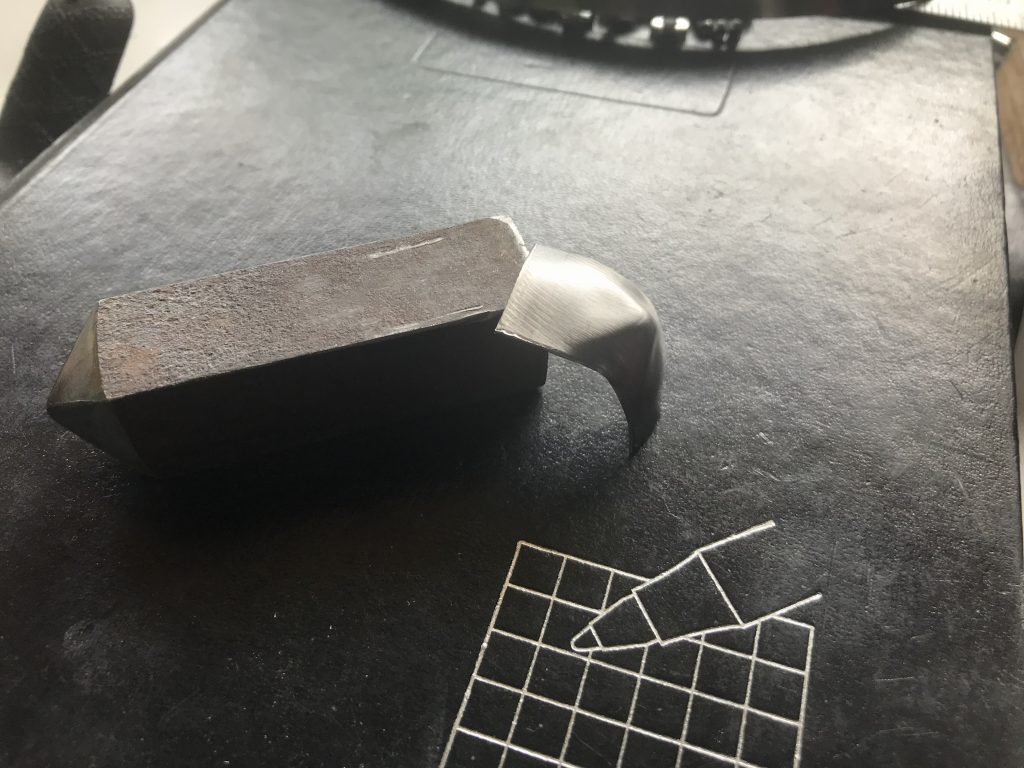

Here are a pair of gauntlets after heat treatment and tempering. Because we used a kiln with very good temperature control we have minimal scaling, and there was minimal plate deformation. To ensure that the gauntlets had minimal issues with deformation they were bolted together and heat treated as a unit, and their movement after heat treatment was “fair” – it should be back to full mobility once we clean up the scale, which is making the gauntlets more than a bit “stickier” than they were before treatment since the fire scale won’t allow plates to “slide”. This is also because we tightened the bolts before heat treatment, and will need to “loosen” the plates by a millimeter or so per joint so that they can freely slide on their slots, since the clamping of the bolts has pulled the plates tighter than we want them to be in actual use.

(To be continued as these gauntlets are cleaned up)